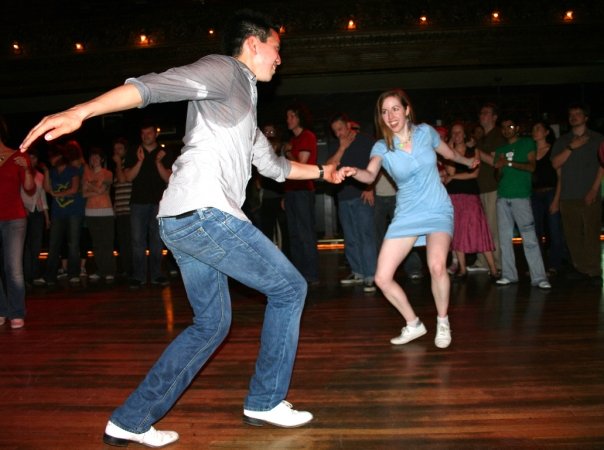

How hard is it to learn swing dancing, and how can instructors best meet the unique needs of beginning dancers? Part 1 of a 2-part series.

Teaching true beginners is different than teaching intermediate and/or advanced dancers

As Rebecca Brightly recently wrote, it takes a while for most people to discover where they fit into the larger lindy hop scene. Like many others, I initially daydreamed about becoming a “rockstar” swing dancer/instructor. Through time, it became clear that my unique gift to the lindy hop world lay in the arena of teaching/encouraging beginning swing dancers at the local level. I also enjoy inspiring all sorts of fun shenanigans (and a few videos) in the process.

I’ve greatly enjoyed teaching classes at Seattle-based HepCat Productions and Mountain View, California based Wednesday Night Hop. After teaching different levels, I’ve come to respect the difference between teaching “true beginners” and intermediate/advanced dancers*. I define beginners as anyone generally in their first 3-4 months of dancing, and intermediate/advanced as anyone who has “graduated” from their initial introductory classes.

Like many others, I originally assumed that teaching introductory swing would be easier than intermediate since the movements taught in intermediate dance lessons are, indeed, objectively more complex than the movements taught in beginning swing lessons. However, a purely moves based conclusion (“the movements in intermediate are more complicated therefore teaching it is harder”) leaves out the monumental mental component that is involved in teaching/learning a brand new skill, particularly a movement-based social and musical skill.

Over time, I have come to deeply respect the unique challenges of teaching novice dancers. Our school system respects the differences between teaching basic skills (such as reading/writing/arithmetic) and teaching advanced concepts by requiring teachers to obtain either an elementary or secondary education certification. Similarly, I would like the swing dance community to respect the difference between teaching “elementary” versus “secondary” dancers.

In the following post, I will use an activity analysis framework to explore in detail what the beginning dance student goes through as they learn this dance in a typical beginning class environment. In a follow-up post, I will then suggest what teachers of “true beginners” should pay particular attention to in order to meet these dancers’ needs. I hope that by the end of these posts the reader will share my respect for the complexity of this role!

What skills must a student learn and enact in a typical beginning swing dance class?

The “OTPF: occupational therapy practice framework” provides a useful tool to explore this question. Among other things, the OTPF outlines all aspects involved when a person performs an activity. It is what I use in my practice to help me determine which component of a patient/client’s condition is causing their problems/successes.

In occupational therapy, “performance skills” are the individual component skills required to perform the larger activity. Let’s take the high-5 as an example: in order to give a high-5, you must:

- Have the requisite motor ability to move your shoulder and elbow through space to approximately get your hands in the right position to initiate the clap;

- Use precision to target your hand towards the other person’s hand (there are different cognitive areas involved in “gross motor” and “fine motor” movements, thus these 2 stages are distinct);

- As you bring your hand towards the other person, you must use your judgment to adjust your aim and velocity;

- Concurrently display appropriate social/emotional skills while doing so (for example, you must somehow initiate the High-5 through communicating with your partner).

Believe it or not, the description I just wrote is actually far more simplified than if I did a true “activity analysis,” but I think it gets the general point across!

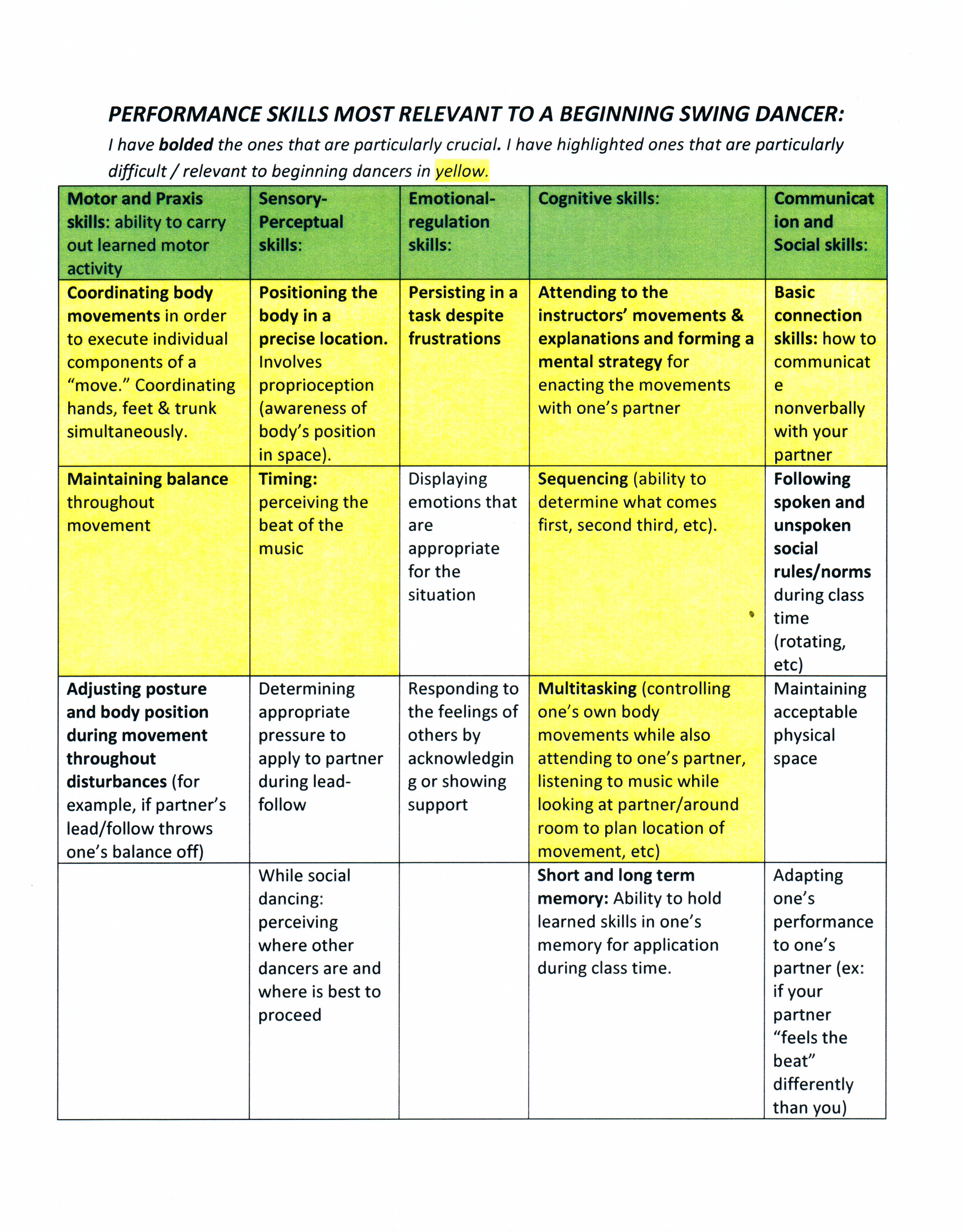

It is useful to consider the individual performance skills required for beginning swing dancers in order to fully explore the unique challenges of teaching them. I have selected factors below that I feel are most relevant to beginning dancers.

Motor & Praxis Skills:

While coordination challenges dancers of all levels, it is of primary difficulty to beginner dancers. It’s particularly difficult for those who lack a background in sports, dance, or other activities that involve coordinating the hands, feet & trunk simultaneously. Beginners are not only learning swing “moves” for the first time, they are also learning how to learn and do moves at the most basic level.

Intermediate/advanced dancers benefit from having learned how to coordinate their bodies through the three plus months of practice they’ve had in a swing dance class environment. This improves their fundamental motor coordination and contributing factors such as balance and the ability to adjust their posture and body position despite motor disturbances. As indicated in the graph above, balance is particularly relevant for a partner dances as we have to learn to adjust to the “disturbance” our partner provides.

Additionally, beginner dancers must learn how to coordinate their bodies in the unique style/manner of swing dance (versus, say, salsa or tango). Even if someone is extremely coordinated from a lifetime of sports or other dance forms, they must learn the movement style and patterns for swing.

For example, the student must learn how to enact the “bounce” from their core/knees, while simultaneously moving their arms in whatever pattern is required for the specific “move.” After a few months of beginning swing lessons, the student tends to become “unconsciously competent” in this area. However, in the beginning they must learn to layer the basic movement style (primarily the “bounce”) and connection style on top of whatever movement pattern is being taught at the moment.

Sensory-Perceptual Skills:

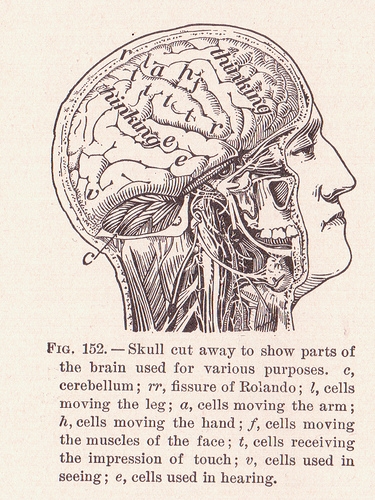

Proprioception (your brain’s awareness of your body position in space) is fundamental to performing any movement.

Many beginning swing teachers (myself included) have at one point or another uttered the cue, “Don’t look at your feet!” However, we must explore why our students look at their feet; it could be that they are shy and don’t want to look at their partner, or it could be that they literally are looking to see where their feet are in space because they haven’t developed a good enough sense of proprioception to trust where they are without using vision to compensate.

There are some great resources out there on how proprioception works and how to improve it. In the case of the typical beginning swing dance environment, I believe it is mainly improved simply through practice. As mentioned in the post I linked to above, your brain creates “maps” of your different body parts, and the parts used most often become larger.

As you practice a given movement with a variety of partners, you gain a better understanding of where your limbs are in space. Thus, beginning swing teachers must pay special attention to how much work it takes for the beginning swing dance student simply to understand where their body parts are in space as they enact a movement.

A second relevant sensory-perceptual skills is a sense of timing.

“Timing” can refer to spacing out your movements so that, for example, you get to the end of the 6 count basic on the 6 rather than the 4 or 8. It can also refer to a basic understanding of the music’s timing outside of any body movement.

One of my biggest challenges has been teaching students who cannot verbalize or perceive “the beat.” My personal experience has been that with repeated exposure to the music and graded practice, it can be improved. For example, start with just verbalizing the beat for the student, then have them practice verbalizing it with you, then have them snap or clap the beat. Regardless of how it can be improved, an appreciation of the role of timing is crucial for a beginning dance teacher as a given class will likely contain some students who cannot perceive or move to “the beat.”

Emotional-Regulation Skills:

In the chart above, I have highlighted “persisting in a task despite frustrations” as a primary emotion-regulation skills crucial for beginning swing dancers. It should go without saying that frustration is an emotion that all beginning dancers will experience at some point, no matter how well regulated their emotions are or how well they are doing in the class.

Frustration is often caused by wishing one could improve faster, or feeling unhappy with one’s partner, or feeling incompetent in one’s own ability to enact the movements that the teachers make look so easy. In order to stick with the task long enough to become competent, the beginning dancer must live in “consciously incompetent” and “unconsciously incompetent” land for uncomfortable amounts of time.

Like many dancers who’ve been around for 5+ years, I sometimes wish I could be a beginner again, but I think we tend to have rosy retrospection. Being a beginner is hard work, and sticking with it long enough to become competent takes a lot of persistence. While frustration is occurs whenever a dancer strives to improve (whether the dancer is a master or beginner), the frustration of beginning dancers is unique because the beginning dancer has no prior experience to provide them with hope that they can improve.

For example, the intermediate dancer can say to him/herself, “Well, I learned the basic Charleston, so I know I can learn tandem Charleston even though it’s hard right now.” The beginning dancer has no prior experience of mastery with this dance to motivate him/herself to continue. They must get the hope from somewhere else; a general sense of optimism, encouragement from a partner or teacher, or a generalized sense that “I’ve learned other difficult things before, therefore I can learn this.”

I will also quickly mention that there is a social-emotional regulation component here as well; one must be able to regulate one’s own emotions while responding to a partner’s experiences. We all know that feeling when a move goes wrong of wondering, “Was it me, or you, or both?” The beginning dancer must learn to act appropriately in this context, which again becomes more comfortable through time as one progressed to intermediate/advanced levels.

Cognitive Skills:

The cognitive load of learning this dance cannot be understated. In addition to mentally organizing the four factors listed above, the beginning swing dancer must also attend to the instructors’ movements/explanations and form a mental strategy for how they will then enact the movements. We’ve all had the experience of watching someone do a move and thinking, “How did they DO that?”

Sequencing

A beginning dancer must learn how to separate the basic movement components from each other when observing the instructors as well as when performing the move themself. It involves a cognitive skill called “sequencing,” which refers to your ability to determine what comes first, second or third. For example, to do a basic 6 count inside turn, does the leader bring the follower in on the 1, 2, or 3 of the beat, or before or after the rock step?

Attention

Attention is a huge area of difficulty for beginning swing dancers. They have to pay attention to every aspect of what they are doing because each aspect is “new” to them. This is in contrast to intermediate/advanced dancers, who don’t have to pay attention to “the bounce,” or other basic movements or even social aspects of the dancing experience, which have become normalized to them.

Memory

Finally, a beginning dance student also experiences a cognitive load on his or her short and long term memory. Our memories don’t only serve to help us recall events in the future, they also help us select and prioritize what is important in the present. I would argue that this prioritization aspect is what puts an extra strain on beginner dancers versus intermediate and advanced dancers.

Through time, a dancer becomes better and quicker at selecting which aspect of a teacher’s actions and words are the most important to attend to and remember in the moment, but in the beginning stages the memory system can easily become overwhelmed and overloaded.

Communication and Social Skills:

I am putting basic connection concepts under “communication,” as I believe that the lead/follow is fundamentally a form of nonverbal communication. The components of the lead-follow connection are not entirely new to all beginning swing students (particularly those with a partner dance background), but in my experience they are new to most. They must learn how the hand to hand, hand to back, and other forms of physical connection allow them to communicate where to position their bodies in space.

This is where the “performance skills” start to differ between leaders and followers, as leaders are primarily responsible for initiating the communication, and the follower is primarily responsible for responding appropriately (without anticipating or back-leading, which I personally struggled with and see many other followers struggle with as a beginner student!).

The leader must attend to how he/she can facilitate the movement for themself and their partner, and the follower must attend to and enact the basic tenets of following (keeping the momentum, responding to the connection, etc).

Connection skills are continually built upon throughout the dancer’s lifespan, no doubt. I would say that they pose a unique challenge to beginners only in that beginner dancers tend to emphasize moves and movement patterns as a whole rather than the underlying connection that facilitates them. If connection is not internalized, the beginning dancer can easily sail through months of classes without realizing that they are not actually learning the partnered aspect of this dance.

As indicated in the graph above, other social skills such as following the unspoken social norms during class (such as rotating appropriately if applicable, introducing oneself to a partner, apologizing if you step on another’s toes, not talking while teacher is talking) are also relevant. Additionally, there may be a strong social motivation to one’s participation in the class (one might be there to socialize primarily rather than to learn the dance), which can either augment or hinder the learning process depending on how it’s channeled.

Conclusion

I hope that the above considerations have renewed the reader’s respect for just how hard it is for a beginning swing dancer to learn the basics of this wonderful dance!

The beginning student simply has an overwhelming amount of factors to attend to, remember, learn from, and enact. Having said that, I do fundamentally believe that beginning swing teachers can adjust their teaching style to these unique demands to make the experience more positive and fun for beginner dancers!

I look forward to providing specific recommendations based on the considerations above in Part 2 of this two-part series.

*For the purposes of brevity (HA!), I’m including everything from intermediate and advanced in one category; I respect that there is a big difference between them, however I wanted to focus my analysis mainly on the question of “how hard is it to learn this skill?” verus “how hard is it to apply what I’ve learned and become more proficient at it?”

**I am including all that may be necessary; understand that someone without every single one of these factors may be able to dance (for example, having hearing or seeing functions is not a prerequisite for learning to dance or dancing, although the vast majority of current swing dancers have those systems in tact).

No Comments

Pingback:

Pingback:

Pingback:

Mary Anne

Thank you for writing this! I am also an O.T., and I’ve been fascinated by how we learn to dance ever since I started Argentine Tango. I agree completely with your emphasis on the difficulty of turning the mental component of what one is attempting into a highly embodied and musical activity, made more difficult with added layers of coordination. Of course I readily ascribe to the common sense/genius of an O.T.’s approach of breaking down the skill to appropriately graded activities to learn and practice right where the student is at. As a musician, I also believe this is possible when it comes to ear training, even hearing the beat and instrumentation. I would love to share ideas with dance and especially Argentine tango teachers. There is something fun too, about tuning our finely tuned instruments – the ones we live in every day!

Cheryl Crow

Thanks, Mary Anne – I didn’t know there were so many OTs who are also dancers, it’s wonderful to learn! Thanks for your perspective about grading skills, as well as breaking down hearing the beat and instrumentation. I think it’s a great idea to share your ideas with Argentine tango teachers, let me know how it goes!

Judy Pritchett

Thanks for a most interesting blog. I too am both a swing dancer and an occupational therapist.

Cheryl Crow

Thanks for your support, Judy, and I really appreciate the enormous amount you’ve done for the dance community! I didn’t know you are also an occupational therapist, that is wonderful.

Ripple Dandelion

Great discussion, Cheryl! I’m a new swing dancer with six or so months under my belt, so I am still very much in touch with the beginner experience. I’m also the mom of a boy with Asperger’s Syndrome and the often-associated sensory processing issues that go along with an autism spectrum disorder. After many years of observing the complexity of the skills that my son struggles to learn (walking in line, following a multi-step procedure, putting things away), I am amazed that we humans are able to learn as easily as we do. Dancing is just so, so much, on so many levels. That’s what makes it so stimulating and satisfying, but HARD. I am looking forward to your thoughts on the best ways to teach dance.

Cheryl Crow

Thanks so much for your response, it’s SO great to hear from a dancer at the 6 month mark! Your experience with your son is also so relevant, as you said…I had the same experience when I worked at a school for children with developmental disabilities. It makes you not take for granted everything you learned with minimal effort! Please let me know if you have any ideas for what worked best for you as a student, as I’d love to make my next article as comprehensive as possible!

Don Baarns (unlikely Salsero)

Very well done.

One point I’d consider is your discussion goes far beyond swing dancing. You could easily just say “partner dancing” instead, and they use swing as your example.

A great read for all partner dance instructors!

Cheryl Crow

Hello Don – Thanks so much for the feedback that many of my points are generalizeable to learning any partner dance. I have learned basic salsa, waltz, 2-step, and a few others but I suppose I did not feel qualified to speak to the process for other dances as I have so much more experience in swing. However, I hope that what I’ve written can be of use to teachers of any beginning class for a partnered dance! Thanks again!

Joy in Motion

Wow, Cheryl, this is fantastic! I love how you’ve broken down so many of the elements that are too often forgotten. I am definitely going to be sharing this.

Body maps are something I could talk about for hours, so I’m glad you mentioned them and provided a link for more reading. I also think it’s fascinating that your brain maps the space around your body and that your brain remaps your body to include the instruments you use, the car you drive, and the partner you connect with when you dance. I recently read The Body Has A Mind Of Its Own (Blakeslee & Blakeslee) and recommend it for those who want to know more. For teachers in particular, understanding at least a little about body maps is highly valuable.

Can’t wait for Part 2!

Cheryl Crow

Hello! Thanks so much for the book recommendation, I will add it to my Kindle list! I love how brain maps provide us with a concrete visualization for how the brain adapts to activity 🙂

Feel free to provide more suggestions for Part 2, I’d love to hear others’ perspectives as well!

Greg

Nicely done. I look forward to part two. 🙂

Cheryl Crow

Thanks, and please feel free to leave any suggestions for Part 2, as I want to be as comprehensive as possible!

Erin Kroll

This is great, and super useful! Haggai shared it on our Teaching Forum FB page, and I know folks teaching beginners in Philly will take tons of practical lessons away from this post!

Cheryl Crow

Thanks so much! It’s wonderful to hear that you have a Teaching Forum. It would be interesting at some point to make a national teaching forum where we could share best practices “from the field,” so to speak. Say hi to Philly for me, I’ve never danced there but a number of wonderful Philly dancers have moved to SF in the last couple years and I have a very positive impression of the place!

smallramblingdancer

As both and OT and a swing dancer, I can honestly say that this is awesome!

Cheryl Crow

Hi! It’s always wonderful to discover another OT who also swing dances, that brings my count up to 6 (including you and myself). I love how OT provides such a comprehensive lens through which you can analyze any activity 🙂 Looking forward to keeping up with your posts!

Calico

Whoa, Cheryl Crow! This is an awesome post. So interesting and thoughtful and well-written. Thanks for sharing it. : )

Cheryl Crow

Hi, Calico! So glad you enjoyed it 🙂 Hope to see you on the dance floor in Seattle during my next visit!

Rebecca Brightly

Thank you for writing this! I’m so happy to have another lens to look at teaching through, albeit with bigger words. I’m with you on considering connection a form of communication. I also like a bunch of other stuff you said, but instead of recapping all of it, I’ll just say “THIS.”

Cheryl Crow

Thanks, Rebecca! I really enjoy all your insights on your blog as well 🙂 I’m glad there are more champions for the new dancer out there, as beginners often get overlooked!