Strategies for Neurotypical People to Develop Empathy for Autistic People

Historically, there has been much discussion about the extent to which autistic people experience empathy. I am using the phrase “autistic people” rather than “people with autism,” per the recommendation from the Autism Self-Advocacy Network. Recent studies indicate that while autistic people may experience and demonstrate empathy in different ways from neurotypical people, they do indeed experience it, sometimes to intense degrees. The debate is well summarized here.

Throughout this discussion, I have observed a curious and glaring omission: what about how and whether neurotypical people empathize with autistic people? One of the basic tenets of social skills is reciprocity, an attunement to the back and forth nature of social interactions. If we are examining how well autistic people display empathy towards others (the majority of whom are neurotypical), it is only fair to ask how and whether neurotypical people are extending the same courtesy back.

Throughout this discussion, I have observed a curious and glaring omission: what about how and whether neurotypical people empathize with autistic people? One of the basic tenets of social skills is reciprocity, an attunement to the back and forth nature of social interactions. If we are examining how well autistic people display empathy towards others (the majority of whom are neurotypical), it is only fair to ask how and whether neurotypical people are extending the same courtesy back.

In my work as a school-based occupational therapist, I make a conscious effort to develop empathy towards the autistic children I serve. It allows me to effectively tailor my approach to a child’s unique needs, helps us develop a stronger connection, and shows that I am honoring their humanity. So, how can a neurotypical person best develop their empathy skills towards an autistic person’s experience of the world? The old saying, “If you’ve met one autistic person…you’ve met one autistic person” comes to mind. There is no one-sized fits all answer, but I will share my top four strategies below. While my strategies are geared towards children, many can be applied to adults as well. I would love to hear readers’ additional ideas and strategies in the comments section!

1) Read Autistic Individuals’ Memoirs and First Person Narratives

I have found first person memoirs to be invaluable in deepening my understanding and empathy for autistic experiences. My favorite books of this nature include:

- Thinking in Pictures: My Life with Autism

- Born on a Blue Day: Inside the Extraordinary Mind of an Autistic Savant

- Carly’s Voice: Breaking Through Autism

- Look Me in the Eye: My Life with Asperger’s

- The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism

Additionally, the following blog posts and websites have powerful first person narratives about what it is like to live with autism (see additional links in numbers 2-6 below as well):

- Power of Words – This video exposes some of the harmful ways that neurotypical people choose words to describe autistic people, in ways that can be hypocritical. For example, an autistic child might be seen as “stubborn” or “noncompliant” when they refuse a non-preferred activity, whereas a neurotypical person would be labelled “persistent.”

- Quiet Hands – This powerful first person narrative about what it feels like to told to quiet one’s “stimming” or “flapping” hand behavior has helped change my perspective on the ethics of a purely behavioral approach to extinguishing these behaviors, when they might serve a purpose to the child and therefore be extremly painful for the child to stop doing.

2) Understand Sensory Processing Issues Commonly Experienced by Autistic Individuals

Imagine a specific environment that is extremely overwhelming for you in terms of sensory and emotional overload, such as the airport or airplane. For me, airports contain the perfect storm of specific fear triggers (such as fear that the plane will run late and safety concerns), in addition to many uncontrollable sensory demands of the environment (too loud, too hot or cold, noxious smells that I cannot escape from, a generally confining environment that is very hard to control, unsavory food, etc).

In order to further develop empathy for autistic people, I ask myself: what if I had to perform the complex tasks I do every day in the presence of intensely aversive sensory stimuli, such as the airport? How would that affect my ability to focus and maintain a calm, alert state rather than feeling anxious and overwhelmed? This is relevant because every day, when an autistic child attends school, they may be entering an environment they find as overwhelming as I find the airport/airplane. It’s easy to see that being expected to perform well in the presence of aversive sensory stimulation quickly puts one into a fight or flight state, which is not ideal for academic or social-emotional learning.

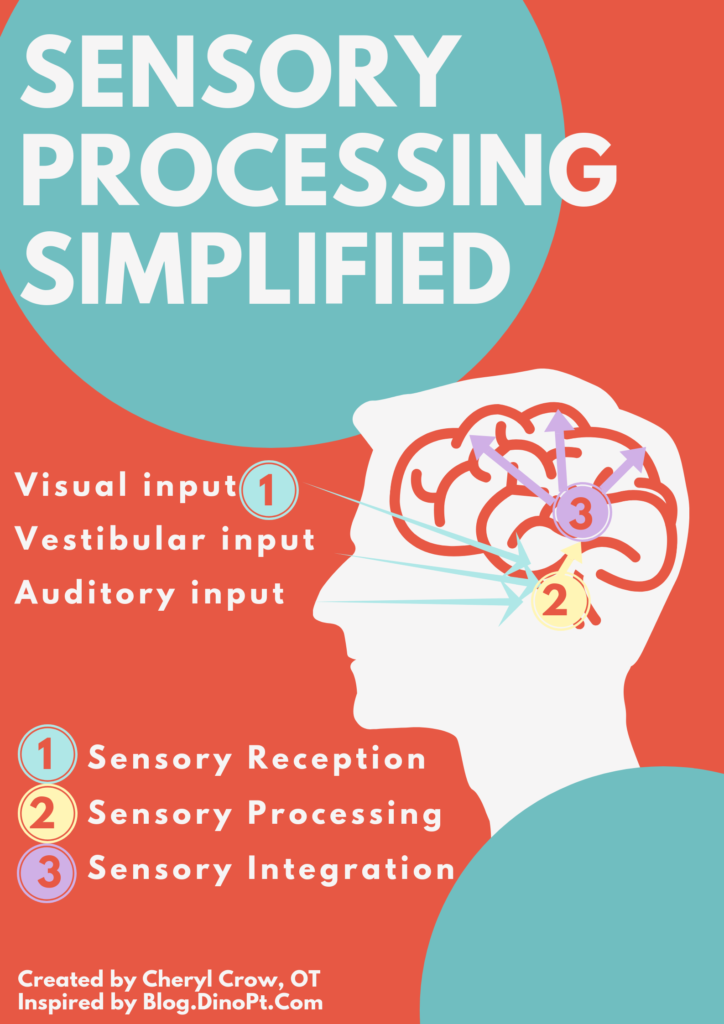

The concept of “sensory overload” is a tad more complex than it may appear on the surface. Sensory processing is the way in which our brains perceive, organize and make sense of sensory input from the five commonly known senses (sight, sound, touch, taste and hearing) in addition to three “hidden” senses: proprioception (body awareness, or our understanding where our body parts are in space), vestibular (balance and motion sense, which starts in our inner ear but can affect many other systems including emotional regulation), and interoception (our internal body sense of items such as hot, cold, pain, hunger and thirst).

For many neurotypical individuals, sensory processing happens unconsciously and smoothly for the most part. As we grow, our brains develop the ability to filter out unnecessary input and to develop “just right” thresholds so that we can function in our daily lives. For example, an elementary student may filter out background noise in the cafeteria in order to focus on a conversation with friends and fluidly shift their focus back and forth between the taste and touch sensations involved in eating, the auditory qualities of the conversation, the visual stimulation of the food, the tactile stimulation of the child’s clothing, other children and background movements, and the body awareness and balance demands of sitting, reaching for foods, and accurately placing them in the mouth.

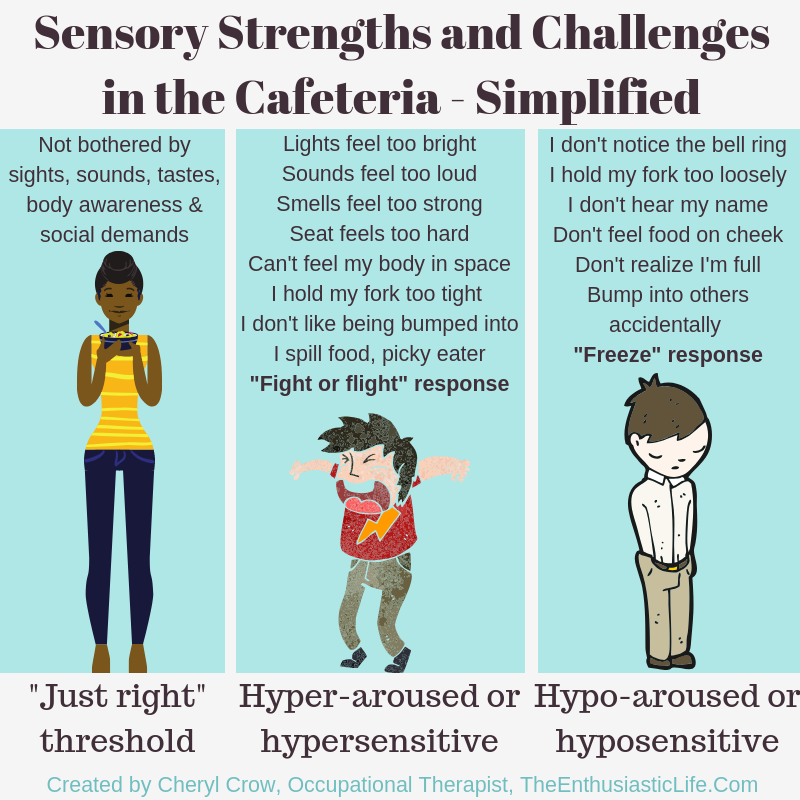

For autistic individuals (and those with a variety of other neurological differences), however, it is well documented that something happens differently in this process, which results in the individual being either “hypersensitive” (detecting and responding to small amounts of input), “hyposensitive” (requiring more input to evoke a response), or a combination of both (most commonly).

Continuing the cafeteria scenario, a child may be hypersensitive to input to the degree that they are distressed by the feeling of the food in their mouth or on their hands or lips, uncomfortable with the feeling of the cafeteria chairs, and overwhelmed by the auditory overload of the lunchroom. A hyposensitive child might have difficulty with sensing where their body is in space, leading them to accidentally bump into others, and they might not perceive that there is food remaining on their lips after the mealtime (which adversely affects them socially). At either end of the spectrum, the child’s potential to participate fully in lunchroom activities is disrupted.

It is important for neurotpyicals to examine the extent to which sensory sensitivities are affecting an autistic person’s experience of life every second of every day in order to truly empathize with their experience of the world. In addition to the airport analogy provided above, I recommend you do the following:

- Watch videos that are specifically designed to allow the watcher to step into the shoes of an individual who has autism and severe sensory challenges. “Carly’s Café (created by a teenager with autism),” and “Can you Make it to the End?” (which is part of the “Too much Information campaign by The National Autistic Society of the UK) are both fabulous examples.

- Examine your own sensory sensitivities and visualize what life would be like if they were more extreme. You can complete the Adult Sensory Motor Preference checklist from the Alert Program, and reflect on your sensory patterns. For example, when I did this, I realized that I have fairly severe smell and auditory sensitivities, to the extent that I find it very difficult to focus or stay emotionally calm in the presence of an aversive smell to me (such as smoke, animal smells, or garbage) as well as aversive sounds (such as the sound of someone else chewing, high pitched sounds, or whining).

- Learn more about sensory processing and sensory challenges. Talk to your local occupational therapist to learn more about sensory processing and sensory issues that might be affecting your loved one with autism, or read more at STAR Institute.

3) Consider the concept of asynchronous development and challenge your understanding of “high functioning” versus “low functioning autism”

It is crucial for those who work with and love autistic individuals (and those with many other unique neurological profiles, including giftedness) to understand the concept of asynchronous development, which simply means that an individual may have a variety of vastly different abilities across different domains such as motor, social, academic, and emotional skills. I’m sure most adults can look back on their own education and see that their grades and abilities were not always consistent across academic areas. We all have our strengths and weaknesses; the case is simply that for children with developmental disabilities / differences, the discrepancy between skills areas is often more drastic than for neurotypical people.

For example, I may be working with an autistic individual who is 10 years old and attending 5th grade general education classes for 50% of the day, yet they may have the impulse control of a toddler, the mathematical and scientific abilities of 9th grader, and the fine motor skills of a 5 year-old. Even that example is a gross simplification, but in general I challenge myself to consider which specific dimension I am evaluating the child on in the moment, and whether I have realistic expectations for them. Remembering asynchronous development helps me further hone in on what is a truly appropriate challenge for a child in a certain skill area.

Simple take-home message: remember that even if a child is “high functioning” in one domain, that does not mean they should be expected to function at high levels across all domains. Rebecca Burgess depicts this concept brilliantly in her comic entitled, “Understanding the Spectrum,” where she draws a series of beautiful visualizations to show her relatively high “functioning” or skills in some areas and “low functioning” or challenges in other areas, and how those areas can be different between individuals, all of whom may share the label “autistic.”

Some additional helpful articles on the topic of asynchronous development are:

- Twice Exceptional Students: Who are they and what do they need? Great introduction to children who are gifted in some areas and also have a learning or developmental challenge in others.

- Autism as a Disorder of High Intelligence: Bernard J Crespi outlines a beautiful theory; in his words: “In this article I describe and evaluate the hypothesis that a substantial proportion of ‘autism risk’ is underlain by high, but more or less imbalanced, components of intelligence.” Basically, it’s a scientifically rigorous way to explore and make the case for autistic children showing asynchronous intellectual abilities (as I understand the article).

- Understanding the Spectrum – Posting again here for those who might have skipped ahead to the additional article links!

4) Try to eliminate the phrase, “If they would just do X” from your vocabulary

It’s not uncommon to overhear adults who work with children on the spectrum saying, “Well, if they can do X, why can’t they just do Y?” This is frequently asked with respect to performing differently on academic or attention-related tasks. “Why can they focus so well on Minecraft, but not on their writing homework? Why can they write well about topics they love, yet refuse to write about topics they don’t prefer?”

It’s not uncommon to overhear adults who work with children on the spectrum saying, “Well, if they can do X, why can’t they just do Y?” This is frequently asked with respect to performing differently on academic or attention-related tasks. “Why can they focus so well on Minecraft, but not on their writing homework? Why can they write well about topics they love, yet refuse to write about topics they don’t prefer?”

I find this line of questioning problematic. I am stubbornly passionate about the right for any human being to not be 100% consistent all the time, because that is unrealistic even for adults, much less children! As someone trained deeply in activity analysis, which is a crucial analytical approach that occupational therapists utilize, the simple but profound answer to the questions above is that the demands of the tasks you are equivalating (e.g. focusing on Minecraft versus homework) are not in fact equivalent. They are not similar tasks for the child, thus the child will perform differently.

Doing a quick empathy exercise should easily reveal this concept to you; do you perform similarly on all tasks that require a certain skill, such as focusing? Do you find it as easy to focus on a boring board meeting in your professional life as it is to focus on a thrilling movie or TV show? Will telling yourself to “just focus” on a boring meeting really inspire the same state of mind as something you’ve specifically sought because it is interesting and relevant to you? If the answers to those questions are no, then why are you expecting a child to show consistency across task domains, particularly when children often lack an understanding of the long term payoff of their school tasks?

Now, the answer isn’t to throw our hands up in the air, or let this phenomenon be an excuse for a child to not try their best even when the task is non-preferred. We all must learn to persist in non-preferred tasks. The difference is that when you approach non-preferred task compliance from the perspective of teaching a child how to persist rather than the perspective of “they just need to,” you position yourself in a supportive, teaching role rather than as a disciplinarian, which is a more humane and often more effective approach.

I strive incredibly hard to eliminate the phrase “they just need to” from my vocabulary with respect to working with individuals with developmental disabilities / differences. The word “just” is derogatory in this context and lacks respect for the fact that every minute of every day is a challenge for many of the children with whom I work. Yes, children with disabilities are human, and all humans have moments where they don’t try their best, and I don’t want a child’s disability to become a get out of jail free card. However, in my experience kids do well if they can, and if they aren’t doing well, it’s because they legitimately lack the skills to do so, and my job is to help them acquire those skills.

How do we best help them acquire the essential skills of nonpreferred task persistence? That’s a topic for another day (and by no means do I have all the answers), but for now I will say that the most important first step is to identify what is the “just right challenge” for this child, make an appropriate goal based on that, and then provide personalized self-regulation, behavioral and attentional strategies to support them in achieving it.

Conclusion

In NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity, Steve Silberman wrote, “By autistic standards, the ‘normal’ brain is easily distractible, is obsessively social, and suffers from a deficit of attention to detail and routine. Thus people on the spectrum experience the neurotypical world as relentlessly unpredictable and chaotic, perpetually turned up too loud, and full of people who have little respect for personal space.” I absolutely love this sentiment because it provokes the reader to empathize with how strange the minds of a neurotypical person might seem to someone with autism.

I became interested in working with children with developmental disabilities / differences at a young age myself, right around middle school. I found myself fascinated by psychological, behavioral and developmental differences and wondered why some children seemed to see the world so differently than I did. Looking back now, I see that my original interest was really one of intended empathy; I yearned to put myself in their shoes and understand how the children in the “resource room” experienced the world.

In my work as an occupational therapist in the school system today, whenever I become overwhelmed (which is often!) I find it very grounding to return to this sense of wonder and empathy. In order to determine how to best support a child, I must first attempt to gain insight into their internal mental state and motivation; at times, it leaves me with more questions than answers, but the trade-off is worth it.

I made minor edits to this page in October 2023 to correct for instances of outdated language, for example “special needs.”

26 Comments

Nat

Here’s another good book for your list, anecdotes from both autistic people and neurotypical relatives.

https://www.amazon.com/All-You-Can-Be-Aspergers-ebook/dp/B01BXD8FYA/ref=sr_1_13?s=digital-text&ie=UTF8&qid=1551008196&sr=1-13&keywords=natasja+rose

Donna Vickers

OMG, I’m not gonna get into a hissy over what may be slightly wrong. Instead I’m gonna thank you for for trying to understand autistic individuals! It’s a start. Where was the empathy for me? It took until I was 40 to “get it”.

Jane Raboin

I really enjoyed this article. I have an Aspergers son and a hyperactive son. A daughter with bipolar and as my youngest daughter says “one normie” her. My asperger’s has a doctorate in nuclear science, my hyper son a bachelor’s in media and a unfinished master’s in media due to drugs and alcoholism, trying to “fix” his feelings and is clean now. He also has an autistic son. I also have a bipolar granddaughter and there’s also an anxiety gene from my mom’s side of the family which I have and many others in my large extended family have. Excuse the pun but it could be worse. Thank God for all His blessings.

Daniel Hope

Interesting I read something in the link “Thinking in Pictures: My Life with Autism”

I think in pictures as well but never thought much about it. I assumed everyone did too?

I might have to find a copy of that and read it.

Pingback:

Pingback:

royalcircleofautism

Reblogged this on The Royal Circle of Autism and commented:

This is a very interesting read …

Pingback:

mpe8691

This piece has a rather common short coming.

That is that whilst the title says “people” the specific examples are about neurotypical adults and autistic children within a school environment. One possibly implied reference to neurotypical children interacting with autistic children. Nothing apparent about neurotypical children and autistic adults. With the most common situation of neurotypical adults and autistic adults being conspicuous by it’s absence.

Some things worth considering include:

Neurotypical “stimming” is called “fidgeting”, with neurotypical “special interests” being called “passions”.

Sensory difficult environments can include offices, shops, bars, nightclubs, sports arenas,…

Discrepancy between skills is present amongst autistic people of all ages. e.g. someone can hold an advanced degree whilst having no idea how to apply for a job.

The likes of “If they would just do X” are actually a bigger issue when it comes to autistic adults. Since more Xs tend to be expected of a 37 year old person compared with a 7 year old person. There’s also variations along the lines of “If you can do Y then you must also be able to do X” and “X is easy, Y is hard & Z is very hard”.

Cheryl Crow

Hello,

Thank you so much for taking the time to comment. I apologize for my delay in response as I just now saw my notification that this comment had been made. You are correct that much of my content was directed towards people working in the school system; my initial goal in writing this post was to provide adults who work with autistic children strategies for developing empathy for them. My intent was to explicitly provide the strategies to neurotypical adults who work with autistic children, and in looking at the post again I feel I have done so (for example, in points 3 and 4 my examples are all of neurotypical adults and autistic children). However, you’re correct that I did not address interactions between neurotypical children and autistic adults, I think that would be an interesting subject for future study – it’s not something I have a lot of experience with at this point.

Great point about how the “if they can just do X” is much more challenging for autistic adults. Thank you again for your thought-provoking post!

Pingback:

Pingback:

Lindsey West (Team Quirky Catholic)

Absolutely love this post – very well written and supported. I hope to utilize the suggestions and adapt them for faith community settings so we can become more truly inclusive of autistic individuals. Empathy and understanding are, unfortunately, often lacking in many faith communities (certainly not all).

Dr. Ellen T. Richer

Hello,

You are so immersed in our world! Excellent article, and thank you.

I am the founder of a small private school dedicated to educating and nurturing Twice

Exceptional learners, the first and only one of its kind on Long Island. In my presentations around Long Island and other places, I emphasize the importance of self- determination or autonomy. I’d love to learn more about your work! You can see our website at http://www.liwholechild.org, too.

Jenwytch

Reblogged this on The Other Side.

Dwight

I love this. I’m a parent of several autistics and have developed an approach similar to yours. I invented a new medical term that helps me and them. It’s NTD or NeuroTypical Disorder, defined as “the inability to think as precisely as autistics do.”

I think it’s ok to ask questions of “why don’t they do this?” as long as the questioner is really looking for the answer instead of just expressing disapproval in question form.

I have read most of the books on your list and love them. But I think it’s important to point out that Carly’s Voice is written by her Dad, not by Carly. I found it to be mostly a sad book because he is so obsessed with “fixing” her that he seems to have missed much of what was right there all along. Carly did write a chapter that is an appendix in that book. In it, she says that the thing that really amazed her is that NO ONE EVER ASKED HER about what she was thinking during that incident that that made her famous and got her on a national news story. She typed “my teeth hurt” on the computer and that was the first time anyone knew that she knew what was going on or had any knowledge of language. And yet years later they had still never asked her for her side of that story. Sad. And a great example of the problem you are trying to fix with this article.

Cheryl Crow

Hello Dwight,

Thank you so much for sharing your thoughts. I love the idea of “NeuroTypical Disroder!”

I completely agree about the importance of questioning behaviors from a place of genuine curiosity, or from a gentle problem-solving stance.

Thank you for pointing out some of the challenging aspects of “Carly’s Voice.” You are absolutely correct that the sections written by her father (which constitute the majority of the book) do not lend particular insight into Carly’s specific lived experience, and they expose some attitudes towards disability that are definitely uncomfortable for me personally to read, and against the notion of celebrating neurodiversity. That said, I find the book incredibly powerful and important to read, as an occupational therapist working in this field, because it paints such a clear and specific picture of how vast the differences can be between outward behavior (described by Carly’s father – rocking, vocalizations, self-harm) and one’s inner state and clarity of thought (as described by Carly). Reading that book was so powerful, it changed how I treat every single one of my nonverbal patients. But yes, I find some of her father’s attitudes problematic. I still am grateful that he honestly communicated his journey, despite the fact that I disagree with some of the ways in which he conceptualized her worth.

Pingback:

Aspergers Girls

Excellent piece. I talk about empathy in my blog and memoir Everyday Aspergers. Our community was just having a long discussion on social media about empathy and this topic. Thanks for sharing. I will share. Sam from myspectrumsuite.com.

Cheryl Crow

Thanks so much for your kind words, and I will check out your blog and memoir! -Cheryl

Aspergers Girls

I shared your post on social media. It got quite a few likes and shares 🙂

Tessa Morton

This is so good. Can I use some of it in a talk I am giving. I will credit all the appropriate people so well written an so valid. Tess

Cheryl Crow

Hi Tess,

Thank you so much for your kind words. You are welcome to use some of these points if you give credit to the original authors (including myself) – I would love to hear who your audience is so that I can track how it is being used and received! Feel free to comment here or email me at my gmail which starts with chcrow. Thanks again! – Cheryl

Pingback:

Pingback:

dyslexic annie

Reblogged this on dyslexic annie's Blog.