Childhood Memories and Lessons that Influence my Work as a Pediatric Occupational Therapist: Part 1

Below, I will share childhood memories that influence my daily work as a pediatric occupational therapist.

Accessing my childhood memories helps me identify with a child’s perspective, even if that child has a specific disability or challenge that I did not experience. When I find myself mystified by a child’s behavior or perspective, I conjure up vivid memories of what it was really like to be a child.

Remembering the complexity of my social, emotional and academic experiences helps build a crucial bridge of empathy between myself and my students.

My lessons are geared towards older elementary aged students who are mostly in the general education setting, as those are the children with which I currently work most often.

1. The Importance of Connecting with a Child’s Emotional Response to their Performance.

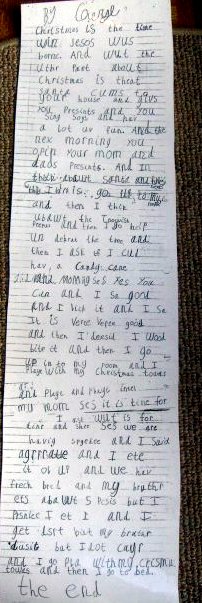

During my elementary school years, I had an unabiding love for horses and a concurrent interest in drawing. As I grew older, I became increasingly frustrated with how badly my drawings looked compared to my vision. I had a very specific image in my mind of how I wanted to draw a horse (see below, left). However, the outcome of my drawings often looked far inferior (see below, right). I remember sitting in the library with one of those “How to Draw” books, trying over and over to draw a good horse drawing, and never getting close to my ideal.

Adding to my frustration and confusion, I found that adults would often praise my drawings as “so pretty!” As someone who took the opinion of adults seriously, I struggled to reconcile their positive assessment with the obviously incongruous reality. I remember concluding that they simply didn’t love horses as much as I did, so they were not attuned to the vast difference between my output and my ideal horse drawing.

The ability to accurately self-assess one’s work is a developmental skill that not all children realistically will have in elementary school. However, I can take a broad lesson from this memory: when there is a chasm between what a child does and what they aspire to do, an adult can serve the vital role of empathizing with the emotion associated with their performance, rather than attempting to soothe them or asserting that their performance is better than it is.

As an OT, I am constantly providing children with the “just right challenge,” just outside their current ability. I may rejoice clinically in their small steps towards improvement, but the child might not see it that way; they may remain frustrated, even if the incremental steps they are taking are objectively significant to me. I have to differentiate my pleasure in their progress from theirs, and identify with their feelings related to their performance in order to fully support the whole child.

This principle is well outlined in the classic book, “How to Talk so Kids Listen and Listen so Kids will Talk.” The main point is to empathize with a child’s current state and reflect it back, rather than negating it or immediately jumping to solutions. For example, if a child shows an adult a piece of work the child is unhappy with, the adult could reflect back to them by saying something like, “You’re frustrated your drawing doesn’t look how you want,” rather than, “That’s a beautiful drawing!”

I hope that the benefits of doing this are self-evident, but in case they are not, here are some reasons that this approach is beneficial therapeutically:

- Empathizing with a child’s self-assessment not only honors the child’s feelings, it also helps strengthen the therapeutic bond between us, as the child may feel more connected and engaged due to my honoring their perception.

2. In examining a child’s emotional reaction to a task, I can more competently address the barriers to their success. For example, if a child is struggling with learning how to zip up a jacket or button their shirt, they might have an outburst of frustration that is more deeply rooted than it initially appears. If I open the conversation to the emotional aspect of their reaction to the task and hold space for them in the moment, I might unveil that they are frustrated because, “My little brother can already do this but I can’t, why are things so hard for me?” or “My fingers don’t work!”

As occupational therapists, we often address motor dysfunction, but I’ve found the bigger barrier to success is often the frustration built from years of feeling like a failure, or feeling confused as to why things aren’t fluid and automatic for this child, as opposed to others. In addressing the emotional component rather than focusing solely on “motor strategies,” I can address a deeper element that might free up mental space for them to ultimately achieve their motor goal more successfully. For example, I’ve had conversations that started about letter reversals for b/d, then quickly transitioned to conversations about why other children “think I’m stupid” or “don’t want to be my friend.” Everything I ask a child to do is hard for them in some way; otherwise, they wouldn’t need therapy. Doing something you’re not naturally good at is intrinsically a frustrating experience for most people, so I try to keep the emotional aspect in the forefront of my mind, even if the specific goal I am addressing is not emotionally rooted. I find that occupational therapy’s roots in mental health are a huge asset for our profession in this respect.

3. If my own reflections didn’t convince you, consider recent research that emotions are integral to learning. As the author of the article states beautifully, “Emotions are not add-ons that are distinct from cognitive skills. Instead emotions, such as interest, anxiety, frustration, excitement, or a sense of awe in beholding beauty, become a dimension of the skill itself.” (Mary Helen Immordino-Yang). In other words, emotions are an important part of the learning process, thus they should not be shoved aside when working on non-emotional goals.

2. Children Need to Know Why They are Being Asked to do Something, or Otherwise Find Meaning in the Task at Hand.

Throughout elementary school, my favorite movie was “The New Adventures of Pippi Longstocking” (see the trailer here). Pippi is a free spirit whose re-introduction into traditional western society after years of living with her father on a sailing ship leaves her frequently confused. While attending formal school for the first time, she quickly becomes distressed. After misinterpreting her teacher’s questions, she tearfully asks, “Why do they ask questions when they already know the answers?” She genuinely doesn’t understand why she’d be asked to solve a problem that a teacher has already solved.

Now, most children who have attended school from a young age understand the cultural norm that in school you will be asked questions to demonstrate your knowledge, as part of the educational process. Regardless, I keep Pippi’s experience in mind because children need to know why they are asked to perform a task or demonstrate competence.

In OT, our end goals are usually functional life skills where the purpose or meaning is self-evident. For example, we help a child learn to hold their pencil correctly so that they can write most efficiently with it. However, we often work on sub-skills that don’t have an obvious connection to our end goal. For example, we might have a child cross the monkey bars and complete Theraputty exercises to improve their hand strength, provide additional proprioceptive input into their hand joints, open their web space and improve body awareness prior to handwriting, to improve their long term writing endurance and precision.

Most children I work with don’t hesitate to question why I’m asking them to do something, particularly when it’s difficult for them. When I take the time to explain the purpose of their OT activities, I get increased buy-in, engagement and compliance on the part of the child. It may feel momentarily frustrating when a child questions why I’m asking them to do something or appears to resist or defy my suggestions, but I try to really challenge myself to maximize everything I can do to help the child find meaning in the task at hand.

The three core innate psychological needs outlined in Self-Determination Theory are critical for me to remember when a child is struggling with motivation: competence (the drive for mastery), relatedness (the desire to connect with others) and autonomy (the need for self-determination or to actively make choices). Usually I can find a nugget of inspiration to draw from by supporting or addressing one of those three core needs.

To explore a topical example in depth: over the last few years, some children have asked, “Why do I need to learn to write by hand if I’m going to spend most of my life typing?” There is a huge international ongoing debate within the occupational therapy and education communities about the role of handwriting in elementary school.

Considerable research indicates that handwriting skills are correlated with improved literacy and retention, thus all other things being equal, I see the case for writing by hand. However, all other things are not equal for most of the children I see. Many children referred to OT have significant barriers that make writing by hand much more challenging than expected. These barriers include visual or fine motor delays (such as Developmental Coordination Disorder), language based learning disabilities such as dyslexia or Specific Learning Disorder with Impairment in Written Expression (sometimes known as dysgraphia, which can be confusing because dysgraphia can also refer to writing legibility impairments that are rooted in fine motor delays such as Developmental Coordination Disorder), executive functioning and/or attention challenges (such as ADHD), spatial reasoning difficulties, and more. When these barriers exist, I help the child and their family make the difficult decision of whether the benefits of writing by hand are strong enough to justify engaging in the laborious process of remediating their handwriting skills, when they have a potentially effective workaround right at their fingertips in the form of a keyboard.

At a recent training on disorders of written expression by Dr. Steven Feifer (whose numerous books on learning disabilities can be found here), I was floored to learn that according to neuro-imaging, written expression is the number one most taxing school activity for a child’s brain, with reading and math being close behind. Dr. Feifer made the case for using accommodations such as typing for children with disorders of written expression in particular, to free up “brain space” that was formerly devoted to the visual-spatial and motor demands of writing by hand. Keyboarding allows for more neurological real estate to be devoted to the higher level executive functioning aspects of written expression such as language processing, organization of thoughts, prioritization, working memory, sustained attention, response inhibition, and more.

Keeping all this in mind: in deciding whether to support the child’s handwriting skills or focus on alternative strategies for written expression such as keyboarding, I must take into account not only the child’s context/environment, age, available technology tools and the extent of their underlying challenges, but also their personal values and preferences with respect to written expression in order to address their need for autonomy. Over the last few years, some students with whom I work have been highly motivated to type, and absolutely flourished with the use of school accommodations such as, “The child can type any assignment of more than 2 sentences.” The option to type has removed considerable frustration and anxiety for these children, and has allowed them to express themselves more fluidly and competently.

I’ve also enjoyed helping other children remediate their handwriting skills, which often brings other secondary benefits. For example, if the underlying barriers are more of a visual-spatial and/or fine motor nature, improvements in these areas will logically extend to many other areas beyond writing. These students worked incredibly hard to remediate their handwriting legibility and speed, and they enjoy the many benefits of writing by hand.

In either case, I have found that when the child has some say as to which approach is taken, there is a sharp increase in engagement and compliance during our sessions. As a child, I was extremely motivated by relatedness; for me, connecting a task to a social outcome was essential for my engagement. However, some students I work with are not quite so socially motivated, and I need to address motivation and engagement from different (sometimes more creative) angles. To learn more about how to address motivation and meaningful engagement in your sessions, consider one of the evidence-based books on the topic such as the Art and Science of Motivation: A Therapist’s Guide to Working with Children, or Goal Setting and Motivation in Therapy.

Concluding thoughts

The world that children today are growing up in today is very different to the world I grew up in during the late 1980s, when playing “Oregon Trail” at the computer lab was the most exciting technological part of my day, and the Encyclopedia Britannica seemed to hold the entirety of the world’s knowledge. Despite the change in technology tools and access to information, many aspects of the learning process and environment have remained unchanged, such as the benefits of adults empathizing with a child’s emotions, and the need to demonstrate why a task or skill is important for a child to acquire. In reflecting on my childhood experiences, I find myself in a better position to identify and address the emotional or motivational barriers a child might be experiencing. I look forward to hearing your reflections and comments as well!

No Comments

Cheryl Morris

Great post Cheryl!

Rick Phillips

I think my favorite punctuation mark is ,,,,,,,,,,,,,, i never met one didn’t think needed three more.