Why and How Do Pediatric Occupational Therapists Play Games?

Why do pediatric occupational therapists (OTs) play games?

Pediatric therapist are often asked why we spend time “just” playing games with our clients. In addition to being engaging to children, games are powerful tools through which we work on a variety of skills including fine motor, visual-motor, gross motor, strength, social, emotional, sensory, and attention, planning and other executive functioning skills.

OTs are experts in adapting games to fit a child’s goals. A competent occupational therapist will never “just play” a game with a child. The game itself and many aspects of the game’s set-up will be consciously chosen and adapted on a minute by minute basis so as to support the child’s progression in a variety of areas.

To demonstrate the myriad ways even a simple game can be used to work on a multitude of important skills, I will use the example of Tic Tac Toe (or “Noughts and Crosses”) below. I will separate skills into categories for the sake of organization, but in reality we hardly ever work on skills in isolation and typically target multiple areas with one activity.

Fine Motor Skills

- Pincer Grasp development: Use small items such as marbles for “x” and “o.” Require the child to use the pincer grasp with their thumb and pointer finger in order to pick the game items up and place them on the board. This helps them further separate the “precision” side of the hand (thumb, pointer and middle finger) from the “power” side of the hand (ring and pinky fingers). Bonus: this also works on hand arch development!

Pincer grasp with a dime. 2. Tongs: Require the child to use a proper grasp on the tongs, which helps them further isolate the “precision” side of their hand. Use fun items for the “x” and “o,” such as different colored cotton balls, beads, game pieces or marbles. Using tongs also promotes an “open web space” which is important for a mature tripod grasp for handwriting. Learn more fun ideas for using tongs in OT at the MamaOT blog here.

- In-hand manipulation: Use small items such as coins for the game pieces. Require the child to start with 2-5 coins in the palm of their hand, then “walk” one coin out to their “pincer fingers” (thumb and pointer finger) while simultaneously keeping the other coins tucked into their palm with their middle, ring and pinky finger. This skills is known as “in-hand manipulation.” It is a great activity for continuing to develop the pincer grasp, in addition to improving overall hand dexterity!

- Stickers: Require the child to peel off stickers to use as game pieces. This works not only on individual finger dexterity but also bilateral coordination, as the child’s non-dominant hand will hold the sheet while the dominant hand peels off the sticker. Learn more about how to use stickers therapeutically here.

Visual Motor and Pre-Handwriting Skills:

- Scissors: Before you start the game, require the child to cut out shapes as the game pieces. Select specific

I instruct a child how to form letters on a vertical surface. shapes at the next level up from their current level of mastery. For example, if they have mastered a square, progress them to cutting out a triangle. Hold the child accountable to grasp the scissors correctly. Using scissors works not only on fine motor skills but also on bilateral coordination as both hands must work together. Learn more about developing scissor skills here.

- Shape development/pre-handwriting: Instead of having a child write Xs and Os, have them draw the basic shapes they are working on mastering. Learn more about the progression of drawing shapes here.

- Vertical Surface: Position the game board on a vertical surface (such as a wall or the underside of a table), which requires the wrist to be in a position of extension (knuckle side of the hand pulled back and facing you, if you are looking at the knuckle side of your hand). As shown in the picture on the right, wax sticks work well, or you can simply use paper and pen/pencil. Learn more about the benefits of working on a vertical surface here and here.

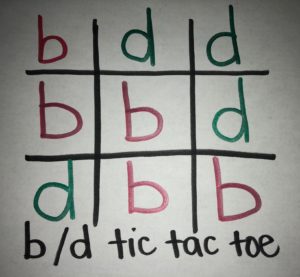

Handwriting:

-

Tic tac toe for handwriting. Practicing writing specific letters or words: Use “problem letters”or words instead of “X” and “Os,” and require the child to write with the desired legibility criteria. Legibility criteria can include: stroke sequence (the order in which the lines are written in order to achieve the letter), size, horizontal alignment (are the letters “sitting” on the horizontal line or “floating” or “dipping?”), and more.

- Pencil grasp: Change the type of writing implement used to promote a more mature writing grasp. For example, using small “stubs” of chalk can promote a tripod grasp, as can using pencils with different grips. You can also use the game as a functional activity by which you can try out different pencil grips which will promote a more efficient grasp for your child.

- Use a tablet (such as the iPad): There are many apps on which you can play Tic Tac Toe. To specifically work on handwriting skills, I would recommend using a stylus.

- Use Tic Tac Toe as a writing prompt: For older children, use a writing prompt such as, “How would you explain how to play Tic Tac Toe to someone who had never seen or heard of the game before?” Apply whatever legibility criteria you are currently using to support improvements in writing performance. This writing prompt would also help work on sequencing, or figuring out how to break an activity down into individual component parts, as well as perspective taking (particularly relevant for persons with an autism diagnosis).

Gross Motor Skills & Strengthening

- Hand eye coordination: Have the child throw a bean bag at a target in order to select which quadrant they are placing their “x” or “o.” Change how far they are standing away from the target to make the task harder or easier to facilitate the “just right challenge.” There is already a product on the market for this concept, called, “Toss Across,” or you can make your own version by following the guide here.

- Balance: Play the traditional paper way but stand on a BOSU ball, balance ball or other unstable surface to improve balance. As always, grade the task by providing different levels of assistance (physical or verbal cues) to help the child reach the next level up of competency from where they currently are.

- Finger/hand strength: Use resistive items for the game pieces such as different colored clothespins or even Legos on a Lego Board!

- Shoulder girdle strength: Working on a vertical surface helps strengthen the shoulder girdle, especially if you work against gravity by positioning the board on a wall or on the underside of a table.

Social Skills

- Social rule following: Any game can be used as an opportunity to understand and follow rules. Set appropriate ground rules before game, such as, “We wait our turn, we don’t offer feedback or suggestions to others unless we are asked, we say ‘good game’ or ‘thank you afterwards.” Hold the child accountable to following those by offering gentle reminders if they are not followed.

-

Patience, frustration tolerance and turn taking are all typical skills improved with games. Perspective taking: Have the child explain the rules to another child, or do an assignment where they “Explain the game of Tic Tac Toe to someone who’s never played so that they understand it.” This forces the child to consider what it’s like to not know what they know, which is a skill that generalizes into many other social contexts. This assignment works really well for games/activities that the child may really love, such as Minecraft. It can be graded up or down (made harder or easier) by the adult “scaffolding,” or giving them hints or leading questions to help them come up with the desired answers.

- Deciding who gets to go first: Learning to negotiate who goes first in a game is an important skill for children. Depending on the child’s level, you can model various ways to choose who goes first (for example, you can have the child whose birthday is coming up soonest go first). As they grow in their social skills, encourage them to take more responsibility/ownership of making these decisions without an adult’s help.

- Reading facial expressions: Use game pieces comprising different facial expressions, and discuss what those expressions represent as you play. You can integrate fine motor/handwriting skills into this version if you have the child first color and then cut out the pieces.

Emotional control and self-regulation skills

- Apply self-regulation program language and tools: While playing the game, apply language from a self-

“Engine speedometer” example from the Alert Program. regulation program such as the Zones of Regulation, Superflex, or the Alert Program. Apply labels to how you feel first, then show how you (the adult) use a tool to regulate your emotions.

For example, you might say, “I just lost my turn, I feel frustrated and in the yellow zone. I’m going to take 3 deep breaths to feel more calm and in the green zone.” The Superflex program has a great “unthinkable” (villain that invades your brain) called “DOF: Destroyer of Fun,” who gets into your brain and makes you overly competitive. The program helps walk children through strategies to “defeat” DOF, which I find particularly helpful! It is effective for some kids to depersonalize what is happening; saying that “DOF invaded my brain and now I have to defeat him” is less personally threatening than saying, “You’re getting too competitive, you need to figure out a way to stop now.”

- Frustration tolerance: Modulate whether you or the child wins, whether they are playing with preferred or non-preferred items, and other aspects to help them work towards becoming more tolerant of frustration.

Sensory Processing Skills

-

Tic tac toe with soap or shaving cream is super fun! Change the materials: Use X and Os with specific tactile input that challenges the child just outside their comfort zone to promote a wider sensory repertoire. For example, if they are very averse to sticky textures, require that they draw some of their Xs and Os with finger paint or shaving cream rather than pencil and paper, and increase that requirement over time. This can be done for aspects other than tactile defensiveness, but I mention a tactile example because they tend to be the easiest to visualize.

- Feeding issues: Use different food items for the X and O pieces. Select items according to the priorities for increasing your child’s food repertoire; learn more about how to approach feeding issues here .

- Change the environment: Modulate the environment (lighting, auditory distractions, visual distractions, smell distractions) either to help the child expand their tolerance of different input, or to make the child more comfortable so that you can best position them to succeed while you work on other areas. For example, if I am really trying to isolate fine motor skills and the child is very distracted by auditory and visual input, I will take them into a smaller and quieter room in our clinic so that they will be less distracted and thus better able to focus on fine motor requirements.

Executive Functioning Skills (not including emotional control, which is covered earlier); particularly relevant for an ADHD diagnosis

- Sustained attention: Challenge the child by playing in a difficult environment for them, such as a loud classroom. Take care to challenge them just beyond their current level of competency; this is known as the “just right challenge.” For some children, playing in the presence of 1 additional person would be very challenging, whereas others are ok with 2-3 others in the clinic but have difficulty with 4 or more. Others will find the challenge not in the number of children present but in how loud the environment is overall.

You can also challenge their attention by holding them accountable to attend to whose turn it is and take their turn without a reminder. Becoming competent in sustaining attention is a vital life skill, so I try to always consider the attention demands of whatever activity I’m doing with a child, and assess whether there is a good fit between the child’s ability and the activity demands.

- Planning/organizing: Have the child plan some or all aspects of the game’s set-up. To make this task easier, give them a set of materials/parameters to work with, such as: “We have to use one of these 4 food items as the game pieces, and a board the size of a 8×11 piece of paper or smaller.” To make the planning/organizing aspect harder, provide a more open ended structure, or introduce the presence of other executive functioning demands such as a time constraint which adds the skill of time management, or the presence of distractions which would upgrade the attention demands.

- Response inhibition: Hold the child accountable to inhibiting extraneous talking, touching of materials or impulsive movements (such as starting their turn before the current person has finished theirs). As with all of these modifications, fit the task to the child’s unique challenges.

- Working memory: Obstacle courses are a great way to work on working memory. For example, you can ask a child to perform a series of 3 different actions before taking each turn on the tic tac toe game, regardless of how it is set up. This will challenge their working memory. If 3 is easy for them, then upgrade the task to 4, and if 3 is too challenging, downgrade it to 2.

Conclusion:

It’s crucially important for occupational therapy professionals to be competent in explaining to parents/teachers/caregivers why we have selected a specific game and set it up a certain way in order to work on improving underlying skill deficits.

As a lay-person, you can play a game without attending to various task demands and the game can simply be a way to pass the time. If the game is set up by a professional who is constantly manipulating various aspects to make it the “just right challenge” to help the child achieve skills, it becomes a powerful tool to help a child function better and achieve their goals.

My goal is always to make therapy as fun and engaging as possible for my clients, but that is never at the expense of working on underlyling skills. I hope this post has helped show you how simple games can be used therapeutically by occupational therapists! Please share your additional ideas for adapting games in the comments section.

No Comments

allgrownupwithjra

Hry Cheryl,

I love this! Thanks for sharing. As a fellow pediatric OT and RA blogger, I hope to share this with my patients and readers a like. Do you mind if I add it to my list of resources on my blog, allgrownupwithjra.com?

Thank you,

Stefanie

Katherine Collmer

Cheryl, You have done such a wonderful job of explaining what we do, how we do it, and why. This is a wonderful resource. I think I will print it and share it with all of my client’s parents and teachers! Thank you.

Cheryl Crow

Thank you so much for your kudos and support, Katherine – I am hoping it will be useful for parents and professionals alike, so I’m glad you will be sharing it with them! I really appreciate your blog as well, thanks again for the support!

Dianna Ferrara

Love this!!!! Thank you so very much for the most extensive explanation of why we choose these activities. You nailed this with your articulate way of explaining all the reasons!

Cheryl Crow

Thank you so much for the kind words, I’m so glad this article has been helpful!

Jessica mcmurdie

What an educational, fun and practical article! Thanks for sharing OT insights into how play can be such a valuable learning tool in therapy.

Cheryl Crow

Thanks for the kind words, and for creating the clinic where I have enjoyed working and learning very much!

shortcakescraps

What a great blog, Cheryl! And such an insightful post. It’s fascinating to see how many ways a simple game such as tic-tac-toe can really help with development. I want to try some of these with little E!

Cheryl Crow

Hi there – Please let me know how it goes, I’m so glad you found this post helpful!! – Cheryl