How hard is it to learn swing dancing, and how can instructors best meet the unique needs of beginning dancers? Part 2 (of 2).

First of all, thank you all for your responses to Part 1, in which I explored the challenges of learning partner dance from the new student’s perspective. I was heartened to learn that so many others are passionate about beginning dancers!

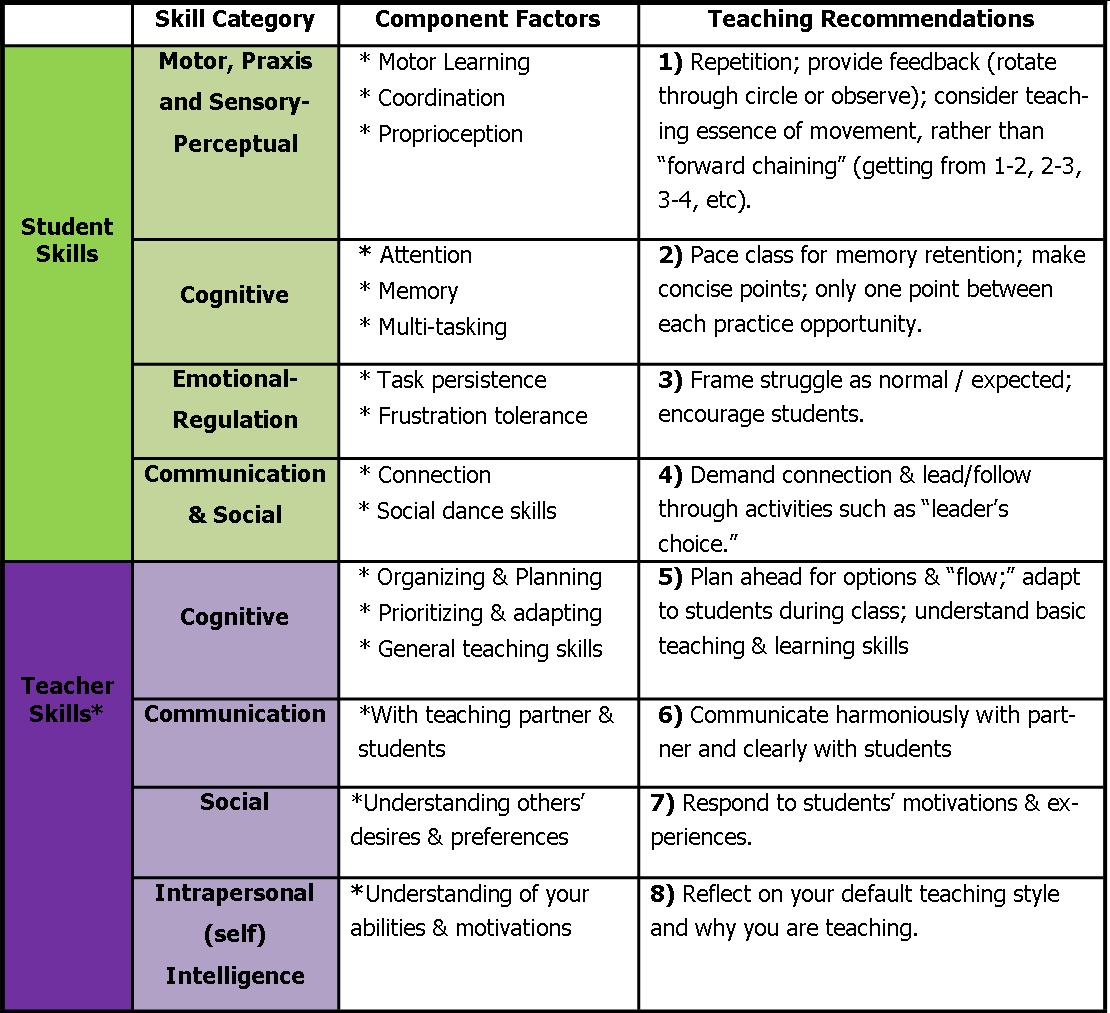

In this post, I will share my humble recommendations for the introductory/beginning dance teacher. These are outlined in the table below. Please note that I am focusing mainly on month-long introductory classes, not necessarily ½-hour “drop-in” classes.

Recommendation 1: Apply motor learning principles.

Motor learning is the process by which your ability to move in specific ways improves semi-permanently through repetition and practice. It’s colloquially known as “muscle memory.” The International Association for Dance Medicine and Science has an outstanding overview of motor learning as it applies to teaching dance.

The main point for beginner dance teachers: repetition is essential for movements to be encoded into long term memory. It can make you itch to give students opportunities to practice skills that seem so simple, but please remember that ample repetition will truly help them solidify what they are learning.

However, mere practice isn’t enough; unless you incorporate feedback, the student risks repeating the same mistakes, which can lead to incorrect motor patterns being encoded into long term memory. Rotating through the circle is the most efficient, effective way a teacher can provide accurate individual and group feedback. As you rotate, observe common mistakes and provide feedback to the class as a whole so that they can practice their movements more competently.

Additionally, consider alternatives to “forward chaining.” Forward chaining generally speaking is the technique of getting from point 1 to 2, then to point 3, then point 4, and onwards until you get to the “end” of the movement (typically the 6 or the 8 in a beginning class setting). This is often the default strategy for dance teachers, and indeed it can be very useful. However, it is not the only way to teach movement patterns, and your students may be more successful if you break down a move to its essence.

Let’s take Charleston as an example. Chris Chapman at Seattle’s HepCat productions introduced me to this method. Instead of starting at the 1 and progressing onward, you could begin by explaining that Charleston essentially is “two kicks per leg.” With music on, have students practice kicking forwards and backwards on the beat, then twice with each leg in front and twice behind. After that, practice one kick backwards then forwards with each leg, then one kick forwards and back.

After students get used to the basic rhythm and cadence of the Charleston, explain that the pattern for side by side Charleston is for the “two kicks per leg” to start with the left leg for leads, right for follows, and to proceed as “back and forward, forward and back” for each leg. Then, explain that the first “back” can be replaced with a rock step, as a variation of a kick. Demonstrate this by having one teacher do a rock step on the 1-2, and the other do a kick on the 1-2 to help the students visualize that they are interchangeable.

When you spend time upfront having students experience and practice the essence of a movement, rather than the “right” placement of their feet and legs at the 1 versus the 2 and 3, they learn the general pattern rather than a specific set of rules. After this pattern is solidified, when they learn a variation (such as hand to hand Charleston), they can layer this specific learning over the general principle rather than having a serial data bank in their brains of “how to do the side by side Charleston,” and “how to do hand to hand Charleston.” This technique actually reduces the students’ cognitive load while also providing repetition of the overall motor pattern.

Additionally, I’m a big advocate of having students practice motor patterns during the warm-up section of class before partnering up. For example, on the day that you teach kick through or hand to hand Charleston, have students practice kicking and pivoting in the same manner during your initial class warm-up. This provides repetition while eliminating the lead and follow demands.

Recommendation 2: Address students’ cognitive needs.

Your feedback should be paced for optimal memory retention and to prevent cognitive overload. Teachers are often so bursting with feedback that we unleash a cascade of “pointers” on students after they’ve only had 1 or 2 opportunities to practice. We think we’re helping, however we get diminishing returns as students become overwhelmed and unable to process our feedback. Here are some concrete recommendations with these principles in mind:

- Make only one “point” for each role between opportunities to practice.

- Before each opportunity to practice, remind students what it is they should focus on/do.

- Before you demonstrate the movements, tell students specifically what to look for to facilitate memory retention.

- Grade your demands up through time. Start with a basic movement, then increase the complexity of the task. For example, have students practice the movement without footwork first and add footwork later. This allows them cognitive freedom to focus on the shape and lead/follow before adding another demand.

-

Brian Zimmer and I teaching in Cali. Provide alternative memory strategies to “1, 2, 3&4, 5, 6, 7&8.” Some students do super well with numbers. Others will fare better with a word-based memory strategy such as “Step, step, triple-step, step, step, triple-step,” others will prefer “right, left, right-left-right,” and others will do best if you simply scat it out, such as “Bah, bah, dee-bee-dah.” I like to alternate between these (with an understanding that some will be annoyed that I’m not repeating it the same way each time). It’s important to provide the alternatives so the students can select which ones to internalize.

Recommendation 3: Frame the struggle as normal / expected.

It’s inevitable: every single student will struggle at some point in the class. Without guidance from the teacher or other experienced dancers, students don’t know what their struggle means and whether it is normal. Here are some ways you can encourage students:

- Provide a supportive, safe environment for making mistakes. Give students a “home base” move to come back to when they have lost the beat, their focus or sense of timing (my personal favorite is just a simple bounce).

- Explicitly acknowledge that learning dance is hard for everyone. I like to have everyone close their eyes and ask people to raise their hands if they have had a hard time learning at least one move or concept in class so far, then have them open their eyes to see how many others are raising them. Of course, if very few people raise their hands, it’s a signal to you to amp up the class!

- Use inspirational quotes or sayings (as deemed appropriate by your own internal cheesiness meter). My favorites include: “Those who don’t make mistakes don’t make much of anything,” and “You wouldn’t worry so much about what other people were thinking about you if you only knew how seldomly they were!” You can also include inspiration on your class websites or handouts. I particularly enjoy this excerpt from Ira Glass: “It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions.”

True story: cell phones didn’t have cameras on them back then. - Share your own experience of learning; I’ve found that students really respond to concrete details, such as, “I couldn’t find the 1 for my first 2 months of classes!” I don’t endorse over-sharing in a class environment, but in this case the personal sharing is in the student’s best interest, as it is meant to motivate and encourage them.

- Avoid over-use of: “Just have fun.” We all want our students to have fun. However, the phrase “just have fun” can trivialize where students are in the learning process. Would you expect a French or Spanish teacher to tell you after your first class to “just have fun” speaking a totally new language? I think that the “just” in the phrase “just have fun” can backfire and frustrate students even further. It implies that having fun shouldn’t be hard at this point in the process, which for many students is inaccurate. Don’t get me wrong: I think there are many ways to encourage fun during the learning process – I just don’t believe that saying “just have fun” is one of them.

-

Me encouraging my student (and future husband) Gabe! Make it personal. Encouragement is often most memorable when it’s specific and personal. Don’t be shy to encourage individuals! It is often very encouraging to students if you can just remember their names. I will never forget the handful of people who encouraged me as a beginner, even if I only danced with them once.

- Promote an optimistic explanatory style My former post details how you can encourage your students to see their mistakes as temporary and “local” rather than lasting and permanent, which is a more optimistic and rational way to interpret their state.

Recommendation 4: Demand connection and address social needs.

Most beginner dancers undervalue connection, as it does not give as tangible a sense of accomplishment as “doing the move right.” I prefer to demand connection and a true lead and follow through activities such as “leader’s choice.” In this exercise, leaders are free to select from a set of formerly taught moves, all of which start the same way. This exercise addresses both roles, as it prevents the followers from knowing the target move.

Beginner followers often pick up on what they are “supposed to do” and enact the “right” movements with complete disregard for what the leader is leading. When you take away the teacher’s command, the followers truly have to respond to the leader’s signals and leaders get immediate feedback on whether they have actually lead the movement they were attempting. International dancer/instructor Nathan Bugh has an interesting blog post about this concept in detail.

The “leader’s choice” exercise also prepares the leader and follower for social dancing. It gives leaders a safe and guided opportunity to practice the difficult skill of selecting which movement to initiate, and t allows followers to practice responding to the leader’s initiation and stopping themselves from anticipating or back-leading.

Additionally, I like to position the introductory class immediately before a social dance and encourage students to stay for a certain number of songs as their “homework.” This proves to students that they can social dance, and also gives them the opportunity to meet other dancers who might provide social motivation to continue participating in the scene.

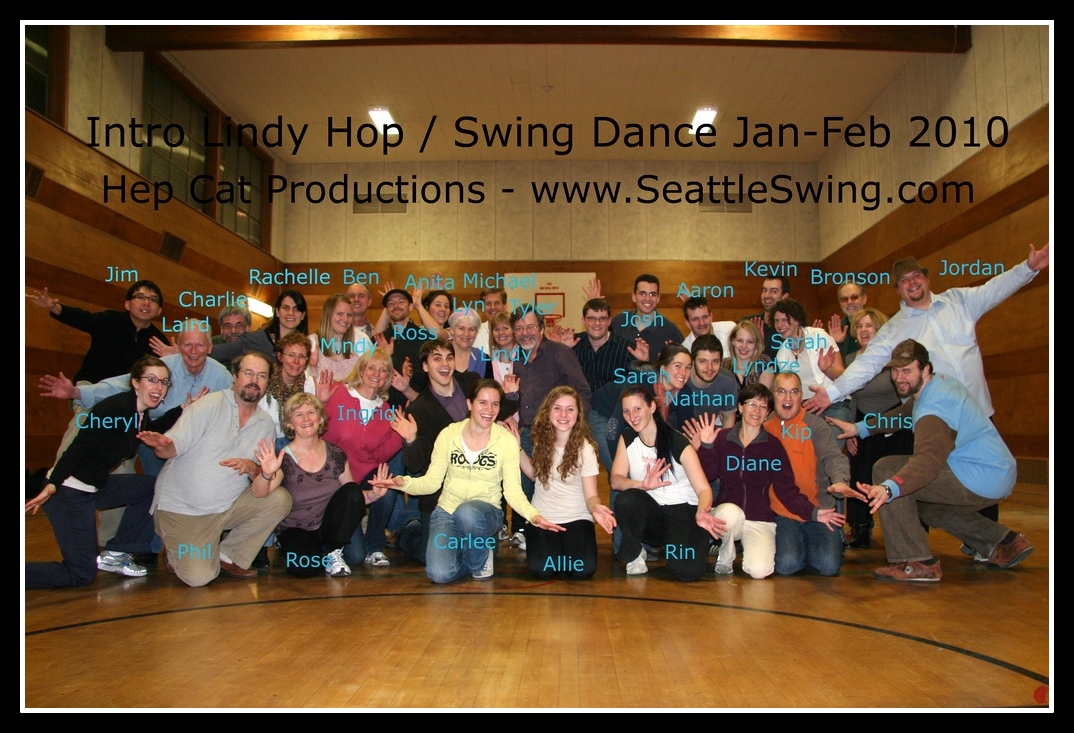

Better yet, photo booths, theme nights, non-dance competitions (like a hula hoop contest on a Hawaiian theme night) and class photos are great ways to promote class retention and facilitate social connections between students, especially when photos of the events are shared on Facebook.

Recommendation 5: Plan ahead and encourage “flow.”

To prepare yourself for the task of teaching beginner dancers, I recommend that you take time to explore some basic principles of teaching and learning, such as the this outline. I particularly like points #4 and 5 on the teaching principles site.

I also recommend that you use the concept of “flow” as a guiding principle for your classes. Flow refers to the psychological state where one’s skills and the challenge of the task are optimally matched. Put simply, you should challenge your students just beyond their current skill level; challenging them too far beyond will produce anxiety, and providing inadequate challenge will lead to boredom.

Regardless of what teaching principles speak to you, I encourage you to spend time upfront planning the following aspects of your classes:

- Pacing: how much time should you spend on each move/concept? I generally chunk my classes into 5-10 minute increments. Even though I end up changing the timing as I respond to the class performance, the practice of chunking the class out helps me plan a sane/appropriate amount of material.

- That being said: prepare alternatives: You can never have too many alternative activities and exercises prepared for your students. Particularly in smaller classes where the mean might be skewed one direction or another (such as fast or slow learners), you should be prepared to grade your task up or down (make it harder or easier) depending on how your students perform.

Recommendation 6: Communication.

It goes without saying that one should communicate with one’s teaching partner harmoniously before and during class. It is pretty obvious to students when teachers are not on the same page, and it can be detrimental if they receive mixed messages from their instructors.

Having said that, direct communication to students is of primary importance. In the teaching role, you will be communicating the mechanics of the lead and follow and of how certain moves/movements work. As you plan your class think about not just what you want to say but how you want to say it; how can you most effectively put these movement concepts into words? Often times, metaphors and analogies are most memorable. I’ll never forget when Nina Gilkenson used the phrase “agile momentum robots” to explain the concept of momentum for followers. It was humorous, succinct, memorable, and got the message across effectively!

Additionally, I encourage you to address how you frame your communication, particularly praise. Research has shown that specific rather than general praise has vast implications for task persistence (read: whether students will stick with dancing, even to the end of your 4 week series). Rather than saying “You’re doing great,” consider specific praise such as, “I like how you rock-stepped on the beat.”

Recommendation 7: Focusing on your students’ actual needs, and the class as the destination.

As an advanced dancer, you might see a beginning dance class as akin to going to the airport: it’s a necessary step towards getting somewhere awesome, but it is not the awesome place itself. Here’s the thing, though: for the vast majority of your students, the class is the awesome destination. Their destination is not “long term obsession with a dance form,” at least not yet; their destination is a 4-5 week novel, exciting concept called a partner dance class that will constitute just one part of their busy lives.

There is a tendency among intro dance teachers to tell students everything they (teachers) wish they had been told as beginners. I implore you to resist this urge. The things you wish you had been told? You only value those things from your lens as an advanced dancer now. Even if someone had told you every useful nugget of information and addressed every mistake you eventually made as a dancer, guess what? You still would have made many mistakes. It’s an inevitable part of the learning process. I think it’s much more effective to focus on where your students actually are right now and address their actual specific needs, not what you anticipate they might wish you had told them a number of months later.

Make this beginner class an awesome destination in itself. Imagine that this introductory series is your students’ only opportunity to experience the wonder that is your form of partner dancing, and accept that they may only experience it as a beginner. Do everything you can to maximize every ounce of fun, enjoyment, and growth you can from those 4-5 hours of lessons! By truly accepting and embracing the experience of learning at this level, you may actually hook them into a long term love of dance.

Recommendation 8: Know thyself.

Self-awareness and reflection will help you identify areas where you can improve as an instructor, and can also help you better complement your teaching partner. Here are some specific areas on which to reflect:

- What is your preferred or default teaching style? Lindy instructors often fall into the “professor/analytical” role or the “entertainer/comedian” role. Recognize your style and consider when it is most appropriate and when it might be best tempered.

-

I tend towards the “entertainer/humorous” style 🙂 Why are you here? I don’t exactly mean why are you on this earth, but why are you selecting to spend some of your time on earth teaching partner dance? Do you teach because you are passionate about helping new dancers learn and have fun? Do you view teaching as a status symbol or a way to gain social currency in your scene? Are you teaching as a default or to please someone else who asked you to? Are you teaching for the money? Do you teach to give back to your community?

None of these reasons is right or wrong, but confronting the reasons will help you determine your overall goals for your class, and whether teaching is ultimately right for you. Although many assume that after you achieve a certain level of proficiency you “should” teach, you by no means have to. If your heart really isn’t into teaching, your students will sense it as well. If your heart really is in teaching, explicitly addressing your motivations can provide comfort or encouragement when the going gets rough.

Conclusion

Just like learning to dance is hard, learning to teach is hard! Being a great dancer yourself will not necessarily translate into good or effective teaching skills. You must translate your passion and knowledge into an understandable form for your students and constantly adjust/adapt to their performance while simultaneously responding/adapting to your teaching partner.

Beginning dance instructors wear so many hats: cultural interpreter, tour guide, salesperson, self-help guru, cheerleader, professor, and even object of affection (lindy crush!). They are constantly pushed and pulled between all the factors discussed above. What’s more important in a given moment, providing more material (“more moves!”) or more repetition of the basics? How much should you teach good form at the expense of “fun,” if some of your students are primarily there to have fun and secondarily to learn dance? Will opening an analytical can of worms spark an “a-ha” moment, or will it overwhelm or bore the class?

You may desperately want your students to share your zeal for your dance, and be confronted with the limits of your own influence when they display apathy or indifference to your efforts.

Here’s the thing, though: despite all the challenges of teaching beginners, it is extremely rewarding. You will witness an amazing transformation as your students go from knowing nothing to being competent in a set of movements by the end of a class series. When a student comes up to me on the social dance floor with a big grin and says, “Look, I did it!”, or I see a formerly awkward student blossom with confidence throughout the course of a class, I feel a sense of pride and joy that words can’t describe. For me, an extreme extrovert, it puts even more social into social dancing. Teaching beginners is a way to ensure I will never become complacent or bored with the scene. It’s one of the many reasons why I dance at all.

Regardless of your interest in teaching new dancers, I hope that my posts have inspired you to see the challenges of learning to dance and teaching new dancers in a new light. Despite the length of these posts I feel I’ve barely even skimmed the surface. Let me know your additional thoughts and feedback in the comments!

Additional References:

Dancing from the Ground Up: Motor Learning Chart

Fleischman’s Taxonomy of motor abilities

* I am leaving out the motor/praxis component for teachers because it’s fairly obvious that a teacher must have the ability to demonstrate the movements clearly and effectively.

No Comments

Pingback:

Kelvin Corbett

Awesome thoughts!!

Awesome Notes!!!

Awesome charts!!!

Your a Star!!

Thank You for Your insight!!!

dogpossum

Gee, this is a great article, Cheryl! It’s really useful and helpful, especially for me as I’m beginning to get my brain into teaching in a big way.

Thanks!

Cheryl Crow

Thank you, dogpossum! Your blog is chock full of awesome. I look forward to hearing more of your thoughts on teaching, I liked your post about the peculiarities of teaching solo jazz!

reyes

OH MY GOSH YOU ARE INCREDIBLE

Cheryl Crow

Aww shucks, thanks for the love, love! <3